The Fragile Predator

New Research Reveals What We've Been Missing About Ted Bundy, BTK, and the Co-Ed Killer

He didn’t look like the kind of man who could terrify an entire community.

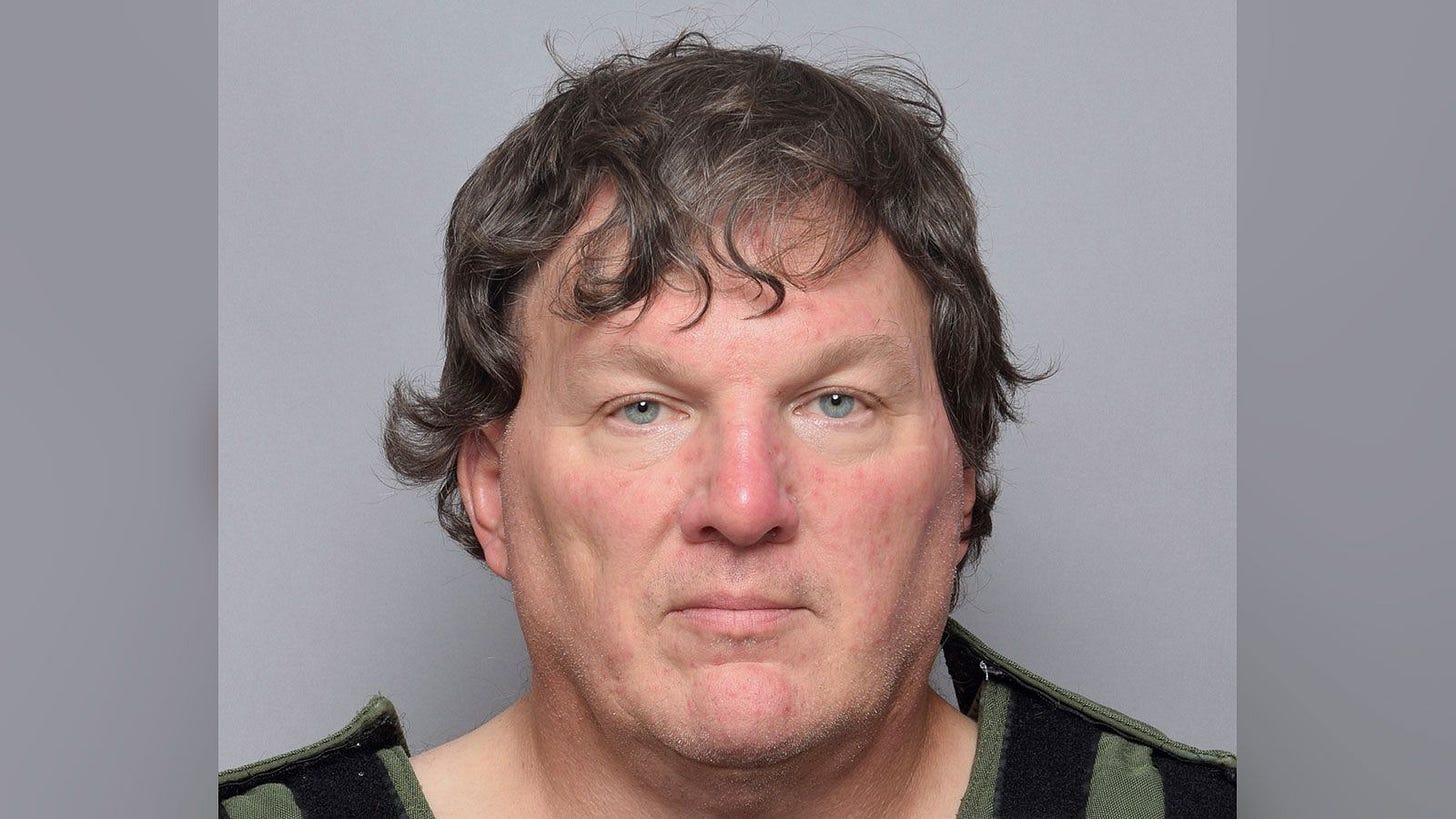

On the morning of July 13, 2023, Manhattan commuters surged along Fifth Avenue with coffees in hand and earbuds in place, focused on the day ahead. No one paid attention to the large, round-shouldered man emerging from the revolving doors of 385 Fifth Avenue. His olive-green jacket strained across his back, collar wrinkled, his gait heavy and uneven. He walked like a man late to a meeting, not like someone about to be surrounded by undercover officers.

His name was Rex Heuermann, and by that evening, his mugshot would be everywhere. He would be charged in connection with several of the Gilgo Beach murders, one of the most haunting unsolved serial homicide clusters in modern American history.

Neighbors described him as “strange,” “hostile,” “a big guy in the shadows.” A former schoolmate said he was “socially odd, the kid you avoided in the hallway.” His coworkers told reporters he was blunt and pedantic, the sort of man who corrected people in meetings and lectured more than he conversed.

He wasn’t charming. He wasn’t magnetic. He wasn’t the crisp, charismatic psychopath true crime audiences have been conditioned to expect. He looked like a man who lived inside himself. A man who had spent years trying to control the world without ever truly belonging to it.

The public struggled to reconcile these pieces. How could someone so awkward, so graceless, allegedly construct and hide such a disturbing world for decades?

Heuermann has not yet gone to trial. But as a forensic psychologist who has studied sexually motivated homicide for more than twenty-five years, I was not surprised by the contradiction. We’ve seen it before.

The Duality True Crime Never Captures

There are men (and it is overwhelmingly men) who present one way in public and live a very different life internally. Men whose psychological architecture contains both brittle grandiosity and wounded fragility. Men who crave superiority but feel deeply defective. Men who need control because they cannot tolerate vulnerability.

Men who can move through the world as two selves at once.

This is the duality true crime never quite captures. And until recently, psychology didn’t fully capture it either. But we’re starting to.

In November 2025, new research was published in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology that made the psychology of sexually motivated serial killers clearer. The study, conducted by forensic psychologist Evangelia Ioannidi and her team at the University of Bamberg, analyzed confessions and interrogation transcripts from 45 male sexually motivated serial killers active in the United States between 1960 and 2021.

What the researchers found challenged some of our long-held assumptions. It demonstrated that the contradictions we see in men like Ted Bundy, Dennis Rader, or (allegedly) Rex Heuermann are not coincidences. They’re not quirks. They are structural. They emerge from a particular blend of traits: four interlocking psychological dimensions of narcissism that create a particularly toxic brew, a fragile, hypersensitive, paranoid core masked by an inflated, aggressive exterior.

Breaking Down the Research: What Vulnerable Enmity Actually Means

Narcissism is a complicated construct. It exists on multiple dimensions that can coexist in the same person. In conducting their study, they used two established psychological frameworks to analyze the transcripts, each of which was split into two subcategories:

Grandiose Narcissism:

Grandiose Admiration: Self-promotion, charm, striving for uniqueness and recognition, need to be seen as special.

Grandiose Rivalry: Devaluing others, aggressive competition, striving for supremacy, seeing relationships as contests to win

Vulnerable Narcissism:

Vulnerable Isolation: Social withdrawal, self-doubt, hypersensitivity, protecting fragile self-esteem through avoidance

Vulnerable Enmity: Paranoia, defensive hostility, fixation on perceived rejection, belief in being unfairly treated, reactive aggression

Here’s what the data showed:

Vulnerable enmity: 84% (the highest of all dimensions)

Grandiose admiration: 76%

Grandiose rivalry: 71%

Vulnerable isolation: 58%

The study, published in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, reveals that vulnerable narcissism (not grandiose narcissism) was actually the dominant form of narcissism in these killers.

Vulnerable enmity was the single most common trait, appearing in 84% of cases. This dimension combines deep-seated hostility, hypersensitivity to perceived slights, paranoid suspiciousness, and an obsessive belief that the world has mistreated them. It’s a seething psychological wound that never heals.

“I expected grandiose traits to dominate, because that’s how serial killers are usually portrayed,” lead researcher Ioannidi told me. “Instead, the most prevalent dimension was vulnerable enmity: deep hostility, hypersensitivity, and fixation on perceived rejection or disrespect. Seeing that this internal fragility showed up even more consistently than the ‘inflated ego’ side was striking, and it reshaped how I understand the psychology driving sexually motivated serial homicide.”

This isn’t just academic hairsplitting. This finding has profound implications for how we profile offenders, conduct investigations, and potentially identify warning signs before the killing starts.

But the real revelation wasn’t just which traits appeared most often. It was how they appeared together. In 62% of cases, grandiose rivalry and vulnerable enmity occurred simultaneously in the same offender. These killers were both aggressively dominating and hypersensitively hostile. And about 60% showed both grandiose admiration and grandiose rivalry together, alternating between seeking validation through self-promotion and asserting dominance through devaluation of others.

Think about what this means: The grandiose presentation isn’t the core driver. It’s the armor protecting a profoundly wounded, hypersensitive self that’s convinced the world has rejected and wronged them. When that armor fails, when narcissistic injuries pile up, the vulnerable enmity erupts into violence.

How Vulnerable Enmity Manifests Across Different Killers

This pattern shows up again and again when you examine the documented behaviors of sexually motivated serial killers, though the balance between vulnerable and grandiose traits varies from case to case.

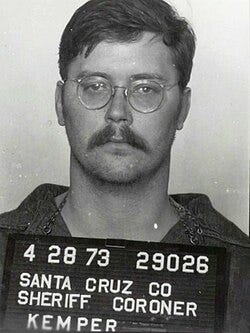

Consider Edmund Kemper, the “Co-Ed Killer” who murdered ten people, including six college co-eds and his own mother. Kemper blamed his innocent victims, claiming they were “flaunting in his face the fact that they could do any damn thing they wanted.” Young women simply needing rides were perceived as deliberately provoking him. He described himself as “a walking time bomb,” saying he could never confront his mother directly and internalized all of his hostility. (In fact, his murders stopped after he killed his mother, suggesting the violence was specifically directed at the perceived source of his humiliation and mistreatment).

But Kemper also displayed striking grandiosity. At his 2017 parole hearing, when asked, “Do you think you’re better than other people?” he essentially said yes, explaining that others are happy with “simpler accomplishments” while he puts more “energy” and “effort” in. During FBI interviews, agents noted “it was often difficult to break in and ask a question” because Kemper talked about himself for hours. He even threatened FBI Agent Robert Ressler (”I could screw your head off and place it on the table”) after the two of them found themselves alone and without guards, then claimed he was “just kidding.” Ressler saw this as a manipulative power play by Kemper to demonstrate superiority and control.

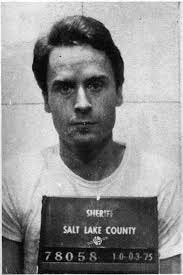

Ted Bundy, who killed at least 30 women, showed a similar duality. After his girlfriend, Stephanie Brooks, broke up with him, he obsessed over the rejection for years. He eventually reconnected with her specifically to dump her in spiteful revenge. In his final interviews, he blamed pornography, society, and violent media for his crimes, never accepting responsibility and suggesting he was somehow a victim of our corrupt culture.

Yet his grandiosity was equally striking. He represented himself at trial despite not finishing law school. His own lawyer, Polly Nelson, said he “sabotaged the entire defense effort out of spite, distrust, and grandiose delusion.” Attorney John Henry Browne described Bundy’s belief that he could lie his way out and charm the judge as a “fatally narcissistic miscalculation.” He even gave interviews, positioning himself as an expert on serial killers, analyzing “the killer” in third person.

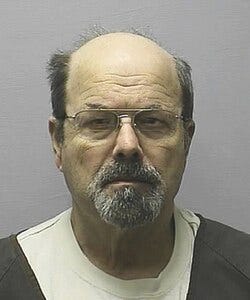

Dennis Rader (BTK), who killed 10 people, is a good example of the variable distribution of the various narcissistic traits. While he showed some vulnerable enmity (writing that killing “hurt me as well as society,” seeing himself as a victim of his own compulsions), his psychological profile skewed heavily toward grandiose narcissism, particularly as it related to his crimes.

Before he was caught, he wrote to the media, “How many do I have to kill before I get a name in the paper or some national recognition?” He created his own “BTK” brand and demanded it be used. Upon arrest, he commented, “I feel like I’m a star right now.” He rejected the term “serial killer” as too limiting for his “accomplishments” and compared himself to terrorists like Osama bin Laden. Rader’s relative lack of vulnerable enmity compared to Kemper or Bundy may explain his more brazen, attention-seeking behavior.

The Mechanism: How Vulnerable Enmity Can Fuel Violence

Understanding the four dimensions is one thing. Understanding how they interact to produce violence is another.

The research suggests that sexually motivated serial homicide isn’t driven by sadistic pleasure alone or even primarily by a desire for power. Instead, these killers are trapped in a toxic psychological loop:

The Grandiose Self (admiration + rivalry) needs constant validation and domination. It cannot tolerate threats to status, competence, or superiority. It sees relationships as competitions to win.

The Vulnerable Self (isolation + enmity) feels defective, humiliated, wronged, and persecuted. It withdraws into fantasy while nursing grievances. It sees the world as fundamentally unfair.

When these two selves collide with rejection, humiliation, or perceived disrespect, violence becomes a way to resolve the unbearable tension. The crime isn’t about the victim. It’s about flipping an internal script from “I am powerless” to “I am powerful,” or more accurately, from “I was humiliated” to “Now I humiliate you.”

This is why sexually motivated serial murders often involve overkill, torture, degradation, sexual humiliation, posing, retention of “trophies,” and reenactment in fantasy. These acts are psychological rituals designed to repair narcissistic wounds.

Forensic psychologist Louis Schlesinger identified the mechanism back in 1998: narcissistic injury. This isn’t just hurt feelings or wounded pride. It’s a psychological experience so threatening to the person’s core sense of self that their entire defensive structure collapses.

For someone with pathological narcissism, these injuries feel existentially apocalyptic because their inflated self-image is the only dam holding back a flood of shame, worthlessness, and murderous rage. The grandiose self promises power, control, and specialness. When reality threatens that grandiose self (through rejection, humiliation, or failure), the vulnerable self’s rage erupts.

One critical insight from the new research is that, in sexually motivated serial killers, vulnerable enmity means this rage doesn’t dissipate. It accumulates. It becomes a chronic, paranoid state of believing the world has wronged you, combined with hypersensitivity to any new perceived slight. Every rejection becomes evidence of a hostile world. Every failure confirms their belief that they’ve been unfairly treated.

This is also why many offenders appear “normal” or even charming until they don’t. The switch between the grandiose outer self and the wounded inner self can be rapid, sudden, triggered by what seems like a minor slight to observers but feels like a catastrophic injury to the offender.

Edmund Kemper: A Case Analysis

Edmund Kemper has been in prison for decades, has given numerous interviews, and is a very intelligent man. As such, his case gives us a rare view into the internal experience of this psychological dynamic.

Every major turning point in Kemper’s life is marked by narcissistic injury and escalating violence:

Age 8: His mother, Clarnell, begins locking him in the basement at night. “The ritual at the end of the day,” he recalled, “was when everyone else went to bed upstairs, and little guy had to go down the old wooden steps along that rough-hewn granite wall, like a castle dungeon. My mother would tell me that I’d get used to the independence.”

Down there with a furnace he genuinely believed housed the devil, violent fantasies toward women began.

Age 14: Desperate, he runs away to find his father in Van Nuys, seeking rescue. His father rejects him and sends him back. This is a crucial narcissistic injury from the one parent who might have provided refuge.

Age 15: Living with his grandmother (who he describes as emasculating him “just like my mother”), he shoots her in the head. “I just wondered how it would feel to shoot Grandma,” he later tells police. When his grandfather comes home, Kemper shoots him too because, as he explains, his grandfather “would be angry” about the grandmother.

Notice: Even at 15, he’s constructing a narrative where his violence is somehow reactive, justified.

Age 20: Released from psychiatric hospitalization. He wants to become a police officer, imagining the authority, respect, and power that come with it. He’s rejected. Too tall. Wrong body type.

He starts hanging out at a cop bar called the Jury Room, befriending police officers. He’s compensating for the rejection (vulnerable) by inserting himself into their world anyway, but in a grandiose way where he’s secretly superior because he’s the killer they’re hunting.

“Cops like me,” Kemper later said, “because they can talk to me more than they can talk to their own wives, some of them.”

May 7, 1972: The first co-ed murders. Mary Ann Pesce and Anita Luchessa, hitchhiking to Stanford. While handcuffing Pesce, Kemper accidentally brushes the back of his hand against her breast. It embarrasses him. He actually apologizes (”Whoops, I’m sorry”) even though minutes later he stabs and strangles her to death.

This moment captures vulnerable narcissism perfectly: He’s so hyperaware of how he might be perceived, so anxious about social appropriateness, that he apologizes for an accidental touch right before committing murder.

“At first I picked up girls just to talk to them,” Kemper explained. “Just to try to get acquainted with people my own age and try to strike up a friendship.”

September 14, 1972: After murdering 15-year-old Aiko Koo, he stops at a country bar “for a few beers.” Before going in, he opens his trunk to look at her body. “I suppose as I was standing there looking, I was doing one of those triumphant things, too, admiring my work and admiring her beauty, and I might say admiring my catch like a fisherman.”

The next day, he has a scheduled appointment with his psychiatrist. He drives there with Aiko’s severed head still in his trunk. The psychiatrist finds him “normal” and recommends that his juvenile record be sealed. Kemper gets a psychological thrill from this; is this not the ultimate grandiose triumph over authority?

January through April 1973: Three more young women murdered. All while living with his mother. All while they’re fighting. All while she remains the central figure in his psychological universe.

“I was paroled to my mother, OK?” Kemper later explained. “When I was fourteen years old, I ran away from my mother. But if you look at that in the overall picture, why did I run away? I wanted to be with my father. I wanted to get away from my mother because I was dreaming, thinking, fantasizing murder. All day long. I couldn’t get it out of my head. She and I, I couldn’t battle with her, because I was very intimidated by her. She had verbal capabilities you wouldn’t believe.”

April 20, 1973: Good Friday. His mother comes home from a party. As he enters her room, she says, “I suppose you’re going to want to sit up all night and talk now.”

Kemper says goodnight. Waits for her to fall asleep. Then he bludgeons her with a claw hammer, slits her throat, and decapitates her. He puts her head on a shelf and screams at it for an hour. Throws darts at it. Then smashes her face in.

He cuts out her vocal cords and puts them down the garbage disposal. The disposal can’t break them down. It ejects them back into the sink.

“That seemed appropriate,” Kemper later said, “as much as she’d bitched and screamed and yelled at me over so many years.”

Then (and this is critical) he doesn’t kill anyone else. He doesn’t run. He calls the police from Pueblo, Colorado, and turns himself in. They don’t believe him at first. He has to call back multiple times with details only the killer would know.

The killing stopped because the narcissistic injury was finally addressed at its source. The person who had rejected him, humiliated him, and made him feel worthless from childhood was dead. The primary wound was closed.

“I said, ‘It’s not going to happen to any more girls. It’s gotta stay between me and my mother,’” Kemper explained. “’ She’s gotta die, and I’ve gotta die, or girls are gonna die.’ And that’s when I decided, ‘I’m going to murder my mother.’ I knew a week before she died I was going to kill her.”

“When they were being killed,” Kemper said about his victims, “there wasn’t anything going on in my mind except that they were going to be mine. That was the only way they could be mine.”

And about keeping their severed heads: “They were like spirit wives. I still had their spirits. I still have them.”

The Fragile Predator

For decades, true crime stories have painted sexually motivated serial killers as cold masterminds. Confident psychopaths. Men drunk on power.

But the science tells us many of them are men split in two: a public self seeking validation and control, and a private self wounded, resentful, and hungry for symbolic revenge.

They do not kill because they feel strong. They kill because they feel threatened, humiliated, erased, and defective. Their violence is not an expression of power. It is an attempt to rewrite their own internal story.

When you watch Kemper in interviews (they’re readily available online and deeply disturbing), you see this duality in real time. He’s articulate, thoughtful, and self-aware enough to warn others with similar urges to seek help. “There’s somebody out there that is watching this and hasn’t done that, hasn’t killed people, and wants to, and rages inside and struggles with that feeling. They need to talk to somebody about it.”

“These offenders aren’t driven only by ego or the desire to feel powerful,” Ioannidi emphasized to me. “Yes, many show grandiose traits, but an equally important part is the vulnerable side: the resentment, hypersensitivity, and deep sense of being wronged. Those two sides working together help explain why their violence is so personal and fueled by control. It’s not about excusing them; it’s about understanding that the psychology behind these crimes is more complex than people usually assume.”

Kemper sounds like someone who’s done extensive therapy and gained real insight. Then you remember: This is the man who described keeping severed heads as “spirit wives,” who called murder his “vocation.”

The new research gives us language we never had: grandiose admiration, grandiose rivalry, vulnerable isolation, and vulnerable enmity. These dimensions reveal the emotional engines beneath the crimes. They expose the fracture lines inside the men. They explain the contradictions that baffled investigators and fascinated the public.

What This Means for Investigations and Prevention

This isn’t just theoretical. Understanding these psychological dynamics has some interesting implications for prevention and law enforcement.

Because grandiose rivalry combined with vulnerable enmity is a reactive, volatile dynamic, confrontational tactics tend to shut down offenders and escalate hostility. The research suggests a better approach: acknowledge perceived grievances, avoid humiliation, build rapport through controlled affirmation, and gently lower defenses. This doesn’t mean coddling. It means using psychology strategically to get information that could solve cases and save lives.

For most sexually motivated serial killers, victim selection is about symbolism, not opportunity. Investigators should consider what symbolic meaning victims held, which groups the offender resented, and what past humiliations might map onto victims and how they are treated; sexually motivated serial killers often reenact shame, rejection, perceived injustice, and powerlessness.

Offenders may not look like predators. Offenders may be awkward, married, employed, socially anxious, bland, uncharismatic, meticulous, or solitary. They may seem the opposite of Hollywood’s charismatic killer. The research says: That may make them more dangerous, not less. Grandiose narcissism without vulnerable narcissism produces arrogance. Vulnerable narcissism without grandiose narcissism produces isolation. But together, particularly when enmity and rivalry pair, they create the brittle, fragile, grievance-driven personality most associated with sexually motivated serial homicide.

What This Doesn’t Mean

This isn’t a redemption story. Edmund Kemper is precisely where he belongs, serving eight concurrent life sentences at California Medical Facility. Innocent people are dead because of him, their families permanently traumatized.

When sentenced, Kemper requested the death penalty, preferably with torture. Capital punishment was suspended at the time. He got life instead. He’s said that if ever released, he’d continue to be dangerous. He’s right.

Understanding the psychology behind his crimes doesn’t excuse them, diminish his responsibility, or transform him into a tragic figure.

It’s also critical to remember what Ioannidi emphasized: “Narcissistic traits alone do not make someone dangerous. These traits exist everywhere in normal life, and most people who show them are not violent. My study looks at how narcissism appears within an already extreme group of offenders, not how to identify future criminals.”

Most people with narcissistic traits (even pathological ones) never hurt anyone. Most people who suffer childhood abuse, rejection, and humiliation don’t become killers. Edmund Kemper represents an extraordinarily rare convergence of factors: severe early trauma, pathological narcissistic vulnerability, grandiose compensatory defenses, sexual sadism, genius-level intelligence that enabled sophisticated manipulation, and opportunity.

The vast majority of people who experienced similar childhoods to Kemper (locked in basements, emotionally abused, rejected by parents) don’t murder anyone. They might struggle with relationships, with self-esteem, with mental health. They might need therapy. But they don’t kill.

What made Kemper different? We still don’t fully know. That’s another mystery to solve.

The Paradox We Can’t Escape

Somewhere in a California prison right now, seventy-six-year-old Edmund Kemper is probably reading a book. Maybe corresponding with another researcher or true crime author. Being articulate, thoughtful, insightful about his own psychology.

And somewhere in his mind, he still has those “spirit wives.” Still thinks about the murders. Still carries both the vulnerable eight-year-old terrified in the basement and the grandiose monster who believed he could possess women only through death.

That little boy locked in the dungeon, convinced he was worthless and unlovable, grew up to bludgeon his mother’s skull and scream at her severed head. The monster and the victim coexisted in the same body, drove the same hands to kill, and spoke through the same voice to confess. That’s the paradox we have to sit with, not to sympathize with killers, but to understand them well enough that maybe, possibly, we can see the next one coming.

Because somewhere right now, there’s probably another rejected, humiliated, enraged person nursing narcissistic wounds and violent fantasies. Understanding that their grandiosity is armor over vulnerability doesn’t make them less dangerous. It might just make them more visible if we’re willing to look past our need for simple monsters and see the complicated, terrifying reality of how human beings break.

“If there’s one thing I know,” Kemper has said, “it’s this: A mother should not scorn her own son. If a woman humiliates her little boy, he will become hostile, and violent, and debased. Period.”

He’s not wrong about the mechanism. He’s just one horrifying example of how catastrophically it can fail.

References

Bonn, S. A. (2014). Why we love serial killers: The curious appeal of the world’s most savage murderers. Skyhorse Publishing.

Browne, J. H. (2016). The devil’s defender: My odyssey through American criminal justice from Ted Bundy to the Kandahar massacre. Chicago Review Press.

Douglas, J. E., & Olshaker, M. (1996). Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s elite serial crime unit. Scribner.

Edmund Kemper Stories. (n.d.). 2017 parole hearing transcript. Retrieved from

https://edmundkemperstories.com

Ioannidi, E., Gauglitz, I. K., Sherretts, N., & Schuetz, A. (2025). Narcissistic traits in sexually motivated serial killers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-025-09780-4

Kershaw, S. (2005, June 27). Rader’s twisted self-image emerges in recordings. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com.

Knight, Z. G. (2006). Some thoughts on the psychological roots of the behavior of serial killers as narcissists: An object relations perspective. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 34(10), 1189-1206. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2006.34.10.1189

Nelson, P. (1994). Defending the devil: My story as Ted Bundy’s last lawyer. William Morrow.

Ressler, R. K., & Shachtman, T. (1992). Whoever fights monsters: My twenty years tracking serial killers for the FBI. St. Martin’s Press.

Schlesinger, L. B. (1998). Pathological narcissism and serial homicide: Review and case study. Current Psychology, 17(2-3), 212-221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-998-1007-6

Thank you for reading this issue of The Mind Detective. If you enjoy this article, please pass it along to one true crime fan. If there’s a case you’d like me to cover, please let me know. Wishing all my readers a Happy Holiday!!!

Is there any corroboration about Kemper’s mother locking him in the basement? I ask because I am skeptical of predators. Maybe the abuse was the other way around. She might have been afraid of him.

It's scary that a major American politician fits into several of the psychological types mentioned.