Could Catherine Griffith Have Been Saved?

Accused Murderer Collin Griffith, Child-to-Parent Aggression, and Assessing Violence Risk During Adolescence

On September 8, 2024, seventeen-year-old Collin Griffith allegedly stabbed his mother to death after an argument. In his 911 call, he told the dispatcher that he and his mother had been in a lengthy argument; she had "fallen on a knife" and was bleeding from her neck. Collin had practice with 911 calls; on Valentine's Day of 2023, he contacted 911 in Oklahoma to say that he had killed his father in self-defense.

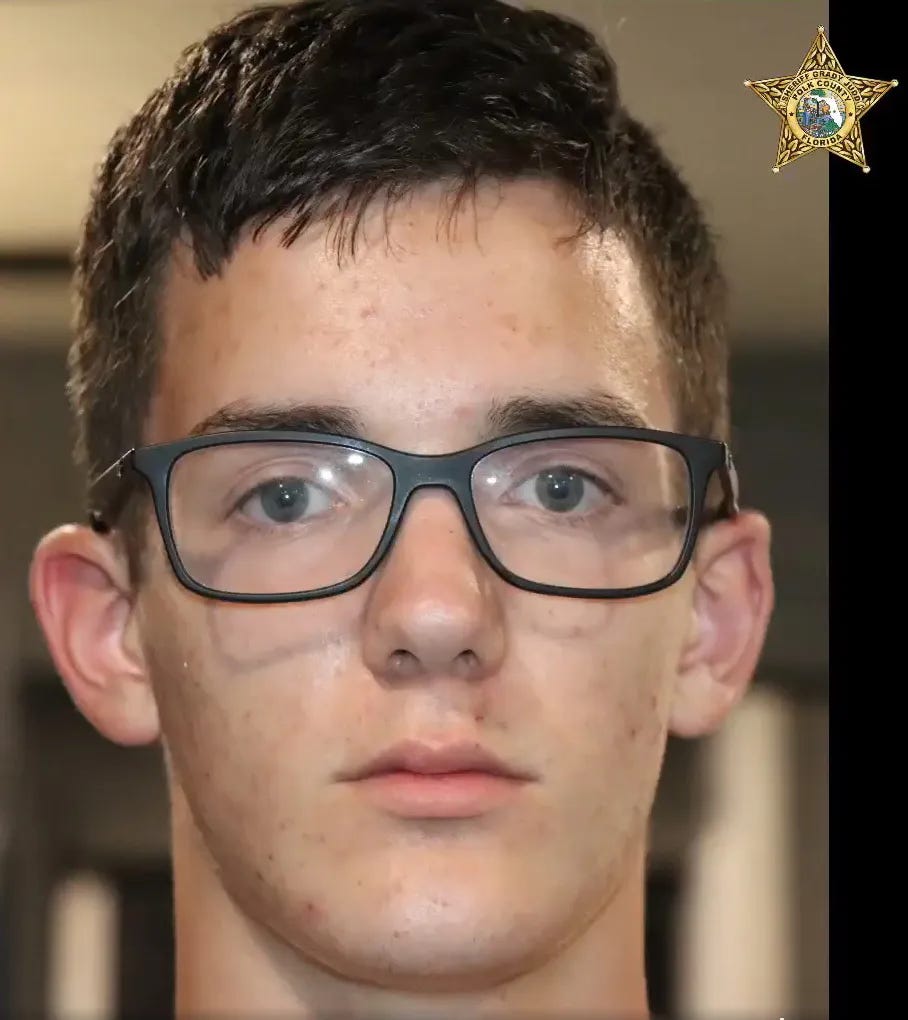

Seventeen-year-old Collin Griffith

In 2019, eleven-year-old Collin Griffith moved from the quiet suburbs of Port Charlotte, Florida, to Stroud, Oklahoma, to live with his father, Charles Robert Griffith. The Griffiths' marriage had ended in divorce, and like many separated parents, they were navigating the complex waters of co-parenting.

Collin's life in Oklahoma remained a mystery to the outside world for nearly three years. His mother, thirty-nine-year-old Catherine Griffith, would later reveal that during this time, her son had been virtually cut off from the outside world, spending 1,041 days in isolation with his father.

39 year old Catherine Griffith

February 14, a day typically associated with love and affection, brought anything but to the Griffith household in Lincoln County, Oklahoma. As afternoon shadows lengthened across the rural property at 354860 E. 900 Road in Stroud, the sound of gunshots shattered the quiet. If they heard anything, neighbors might have dismissed it as routine target practice in the countryside. But inside the Griffith home, a family tragedy was unfolding.

Collin, now 15, had just shot his father. Twice. Once in the chest and once in the head. When Sheriff Charlie Dougherty and his deputies arrived at the scene, they found a situation that defied easy explanation.

Collin's initial account painted a picture of self-defense. He claimed his father had cornered him in a bedroom, forcing him to reach for a gun and fire. However, as Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation (OSBI) agents combed through the crime scene, they began to notice details that didn't align with the teenager's story. The physical evidence told a different tale that raised more questions than answered.

In the days following Charles Griffith's death, Catherine navigated a surreal situation. Her ex-husband was dead, and her son was facing potential murder charges. Collin swore his life had been threatened. Despite the cloudy circumstances, Catherine's maternal instinct kicked in. She paid $50,000 for Collin's bond release, which was made on the condition that he wear an ankle monitor.

As winter turned to spring in 2023, things were looking up for the Griffith family. The charges against Collin were dropped. Catherine could bring her son home to Florida and attempt to piece together their fractured lives.

The reunion, however, was far from smooth. By September, the cracks in their relationship were becoming apparent to those around them. On September 11, 2023, a concerned school officer from Florida Southwestern State College felt compelled to request a mental health check at the Griffith home. Collin, now attending school in Florida, had made a startling claim: his mother had pulled a gun on him during an argument.

Catherine adamantly denied Collin's claim. From her perspective, the conflict was a typical parent-teen disagreement; she had confiscated Collin's phone and AirPods, a punishment for his failing grades. But the incident was serious enough for authorities to place Collin in protective custody for a mental health evaluation under the Baker Act.

The following day, Catherine spoke with a juvenile intervention detective about how bad things at home were. She had been reaching out to mental health facilities across the state, desperately seeking help for her troubled son. Collin's behavior was scary. He had threatened self-harm and violence against Catherine if he was forced to return home. He had also threatened to kill his therapist if she diagnosed him with a mental illness.

Collin was diagnosed, with PTSD and a personality disorder. [Technically, a personality disorder cannot be diagnosed before a person is age eighteen, even if the characteristics are glaringly obvious. The reason for this is that this diagnosis, by definition, describes a longstanding pattern of behavior, and the clinical argument goes, we should not diagnose maladaptive traits that a teenager may grow out of]. Catherine increasingly found herself walking a tightrope, trying to balance her son's needs with her own safety and well-being. She clung to the hope that she could save her son.

Catherine's Death

The fragile peace in the Griffith household held up through the winter and into the following summer. There were bright spots; he graduated early from high school and earned eighteen college credits well ahead of most of his peers. But on September 8, 2024, in a cruelly ironic echo of the tragedy from the previous year, violence once again visited the family. This time, the setting was the Hamptons, a typically tranquil over-55 community in Auburndale, Central Florida.

Neighbors would later recount a disturbing scene. Collin, now 17, was seen arguing with Catherine outside their home. The verbal altercation quickly escalated, with witnesses reporting the horrifying sight of Collin dragging his mother inside by her hair. Catherine's pleas – "Let me go!" – rang out, a chilling foreshadowing of what would come.

Inside the house, beyond the view of neighbors, the situation took a deadly turn. Later that afternoon, Collin once again dialed 911 call, his voice eerily calm as he reported a fight with his mother, stating she was "bleeding from the neck." Police arrived at the scene to find a blood-covered Collin and Catherine on the floor, dead from a stab wound to her neck. The scene bore little resemblance to Collin's account of events, a discrepancy that medical examiners would confirm in the following days.

Collin's grandmother, sharing her insights with investigators, painted a picture of a long-simmering tension in the household. She recounted instances of Collin being physically and verbally aggressive with Catherine, a pattern of behavior that had escalated over time. Today, Collin Griffith sits in custody, charged with the murder of his mother. The legal process is ongoing, with many questions yet to be answered. But beyond the courtroom, the Griffith family tragedy raises profound questions about family dynamics, mental health support for troubled youth, and the long-lasting impacts of trauma.

Is Collin Common?

Research indicates that violent behavior is surprisingly prevalent among adolescents. Studies show that approximately 20-25% of teenage males and 4-10% of adolescent females engage in at least one serious violent act every year ; the peak age for serious violence is between fifteen and sixteen years old. These acts can range from physical assaults to more severe forms of violence, including weapon use.

But when most of us think of violent teens, we think of gangs, bullying, or school shootings. But it happens more often than you think. A 2018 study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence found that approximately 10% of U.S. families experience physical aggression from adolescents toward their parents; the victim is most often the mother. This violence manifests in various forms, from pushing, slapping, and punching to more severe acts like kicking, choking, or assault with household objects or weapons. Parents report instances of property destruction, having phones smashed during attempts to call for help, and being threatened with knives.

The adolescent years can be tough on the parent-child relationship as a teen struggles to transition from a dependent child to an autonomous adult. Most families have bumps along the way; few involve serious violence. A 2023 study examined 252 families in which parents or caregivers were dealing with challenging behavior from their children. Some of these families were experiencing violence, while others weren't. For each family, they assessed the children's behavior, the parents' feelings, and how the family interacted.

Researchers made an important discovery; they found that families experiencing child-to-parent violence could be divided into two main types; "low-proactive" and "high-proactive.

The Pressure Cooker Blows

In the "low-proactive" families, parents typically held the upper hand. The children were closely supervised, and the parents were usually in control. In fact, the children sometimes felt as if the parents were too controlling, resulting in the child feeling anxious or frustrated. The child might then lash out reactively or when emotions got too intense.

The violence in these families tended to be less severe and less planned than in the "high-pressure" family. It was more like the child reacted to something rather than deliberately tried to control their parents. Imagine a pressure cooker slowly building up steam. In these families, the child's aggression might be like that steam suddenly bursting out when the pressure gets too high.

Violence Becomes a Tool

In the "high-proactive" families, the violence was more frequent and deliberate, as if the child was using it as a tool to get what they wanted. The children typically had more freedom and less supervision, and when parents tried to discipline their children, it didn't seem to work. It's as if the typical parent-child roles had been flipped upside down, with the child taking control through aggressive behavior.

Children in "high-proactive" families tended to have troubling personality traits. They were more likely to be callous or uncaring towards others, as well as overly self-centered. They were more easily irritated. These traits might make it easier for them to use violence without feeling bad about it and harder for them to respond to typical discipline in these families. They were also more likely to be aggressive towards siblings and peers.

Over time, these parents reported feeling helpless and frightened. Unsure of what to do, they withdrew or used harsh discipline out of frustration. This response often led to the child using more violence to maintain control, creating a vicious cycle that was hard to break.

The Plot Thickens and Broadens

While there were distinct differences between the two types of parent-to-child violence, researchers found that in all these families, children used different kinds of violence to solve various problems:

Planned, deliberate violence to get something or control others.

Reactive violence is a defensive reaction to something like feeling controlled or criticized.

Affective violence in response to strong emotions or anxiety.

So, even in the "low-proactive" families, children sometimes used proactive violence, just less often. And in the "high-proactive" families, children used all types of violence more frequently. This finding shows that child-to-parent violence is not a simple problem with a simple solution. It's complex, with different types of violence often happening in the same family.

An alarming discovery was that children who were violent at home, especially in "high-proactive" families, were often aggressive in other settings, too, indicating that child-to-parent violence isn't a simple or isolated problem. It's often part of a larger pattern of aggressive behavior that extends beyond the family.

Parents are often reluctant to reach out for help when they have a violent child at home. They're afraid of being judged, ashamed of what they frequently see as their "failure," and worried about what might happen to their child if they speak up. I've also seen parents try their best to get help, only to discover nowhere for them to go or no one knows what to do. At least, not until it's too late.

How Can Forensic Psychologists Help?

The majority of violent teens do not continue this pattern into adulthood. Those who do wind up in prison. Some parents, like Catherine Griffith, don't live to find out. As forensic psychologists, we've got to help families who are experiencing child-to-parent violence as early as possible so we can intervene, starting with a violence risk assessment.

We know a lot about teen risk factors for future violence: past violent behavior, witnessing domestic violence, experiencing childhood physical abuse, substance abuse, anger management problems, and association with delinquent peers. We also have helpful assessment tools like the SAVRY to help us evaluate risk and protective factors in individual teens.

While structured tools like the SAVRY provide valuable information, we also need a comprehensive understanding of the individual's violent behavior:

The function of the violence: Understanding why the adolescent engages in violent behavior. For instance, an adolescent might use violence as a means of gaining respect or status among peers.

The underlying emotional and psychological needs. Identifying unmet needs that may drive violent behavior. A young person with a history of neglect might use violence as a way to assert control or seek attention.

Family Dynamics and Attachment Issues: Examining how family relationships contribute to violent behavior. An adolescent with an insecure attachment style might struggle with emotional regulation, leading to aggressive outbursts.

Sociocultural Context: Considering how cultural factors and societal norms influence the individual's behavior. For example, an adolescent from a community where violence is seen as a legitimate problem-solving tool may be more likely to engage in violent acts.

We can then use this information to formulate targeted, effective interventions that address not only the overt violent behavior but also the underlying needs and deficits driving that behavior.

The Bottom Line

As our understanding of child-to-parent violence continues to evolve, so must our approaches to assessment and intervention. Forensic professionals can mitigate violence risk within families and the broader community by staying informed about the latest research and best practices and turning their evaluation results into individualized plans for intervention and treatment. If, as Ashley Montagu said, the family is the basis of society, we all benefit when a family tragedy is averted.

As always, thank you for reading this issue of The Mind Detective. Please pass this free newsletter along to your true-crime-following friends!

Why didn't Catherine griffith's neighbors call 911 when two of them witnessed her son dragging her inside the house??

It is not that the families fail to ask for help. There is NO HELP! You wrote that the mother looked everywhere for treatment when Collin didn’t want to return home because she was afraid. Even the police failed to grasp why he was returned home despite making threats. There is nowhere for them! Not even a place to warehouse them. Moreover…There is absolutely no effective treatment for “conduct disorder” or psychopathy. Even “autism” with various aggressive or personality disorders is not particularly amenable to treatment in those with callous and violent traits.